Giulio Alberoni on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

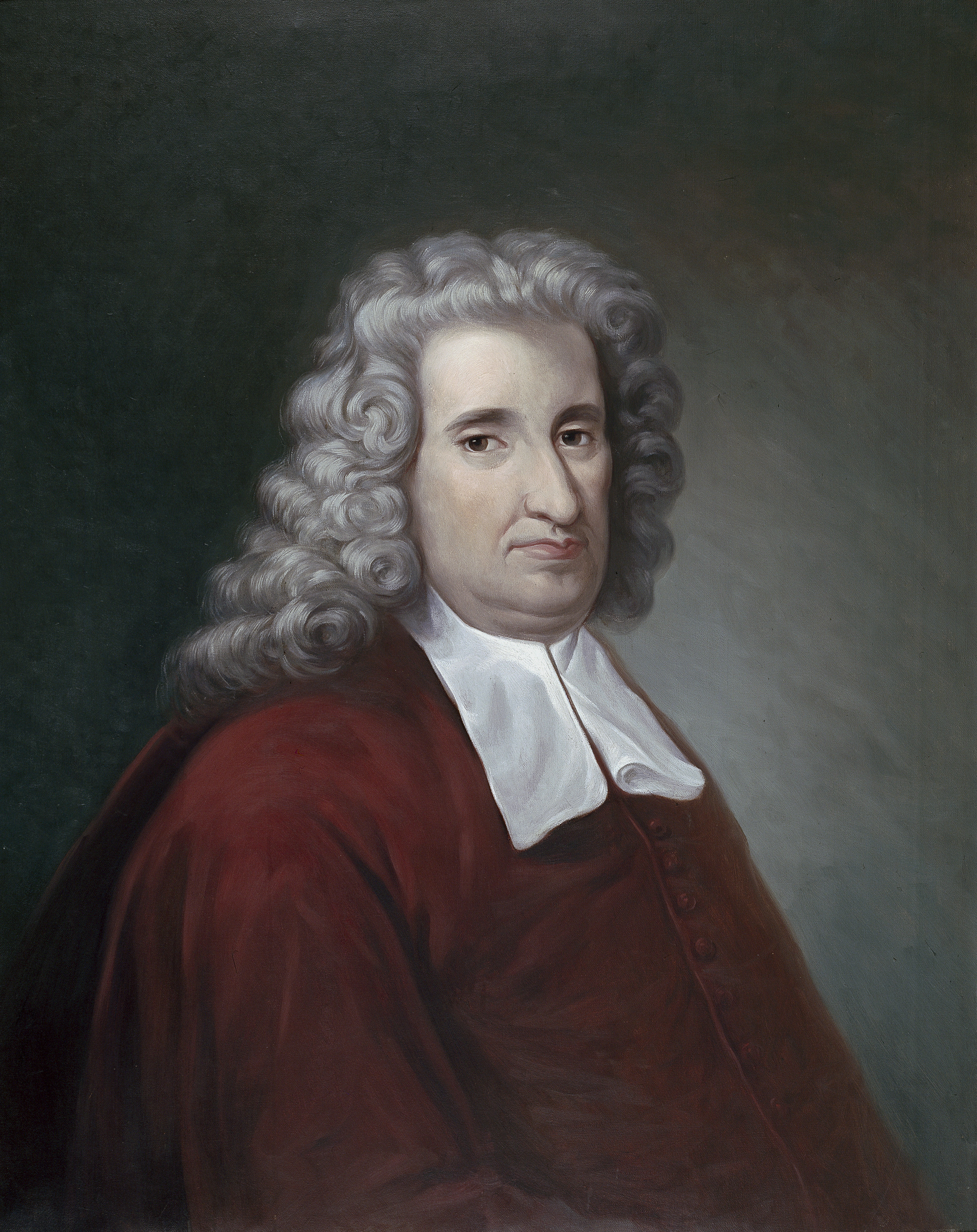

Giulio Alberoni (30 May 1664 OS – 26 June NS 1752) was an Italian

Giulio Alberoni (30 May 1664 OS – 26 June NS 1752) was an Italian

Alberoni accompanied Vendôme to Spain as his secretary and became very active in promoting the cause of the French candidate

Alberoni accompanied Vendôme to Spain as his secretary and became very active in promoting the cause of the French candidate

He went to Italy, escaped from arrest at Genoa, and had to take refuge among the

He went to Italy, escaped from arrest at Genoa, and had to take refuge among the

''Catholic Encyclopedia'':

Giulio Alberoni

Giulio Cardinal Alberoni

Conclave of 31 March – 8 May 1724

Collegio Alberoni, Piacenza

{{DEFAULTSORT:Alberoni, Giulio 1664 births 1752 deaths People from Fiorenzuola d'Arda 18th-century Italian cardinals Grandees of Spain

Giulio Alberoni (30 May 1664 OS – 26 June NS 1752) was an Italian

Giulio Alberoni (30 May 1664 OS – 26 June NS 1752) was an Italian cardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**''Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, the ...

and

statesman in the service of Philip V of Spain

Philip V ( es, Felipe; 19 December 1683 – 9 July 1746) was King of Spain from 1 November 1700 to 14 January 1724, and again from 6 September 1724 to his death in 1746. His total reign of 45 years is the longest in the history of the Spanish mon ...

.

Early years

He was born nearPiacenza

Piacenza (; egl, label= Piacentino, Piaṡëinsa ; ) is a city and in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy, and the capital of the eponymous province. As of 2022, Piacenza is the ninth largest city in the region by population, with over ...

, probably at the village of Fiorenzuola d'Arda

Fiorenzuola d'Arda (; egl, label= Piacentino, Fiurinsöla, or ) is a city and ''comune'' in Italy in the province of Piacenza, part of the Emilia-Romagna region. Its name derives from ''Florentia'' ("prosperous" in Latin). The "d'Arda" portion r ...

in the Duchy of Parma

The Duchy of Parma and Piacenza ( it, Ducato di Parma e Piacenza, la, Ducatus Parmae et Placentiae), was an Italian state created in 1545 and located in northern Italy, in the current region of Emilia-Romagna.

Originally a realm of the Farnese ...

.

His father was a gardener,"Alberoni, Giulio''Chambers's Encyclopædia

''Chambers's Encyclopaedia'' was founded in 1859Chambers, W. & R"Concluding Notice"in ''Chambers's Encyclopaedia''. London: W. & R. Chambers, 1868, Vol. 10, pp. v–viii. by William Chambers (publisher), William and Robert Chambers (publisher ...

''. London: George Newnes

Sir George Newnes, 1st Baronet (13 March 1851 – 9 June 1910) was a British publisher and editor and a founding figure in popular journalism. Newnes also served as a Liberal Party Member of Parliament for two decades. His company, George Newnes ...

, 1961, Vol. 1, p. 223. and he himself became first connected with the church in the humble position of a bellringer

A bell-ringer is a person who rings a bell, usually a church bell, by means of a rope or other mechanism.

Despite some automation of bells for random swinging, there are still many active bell-ringers in the world, particularly those with an adv ...

and verger

A verger (or virger, so called after the staff of the office, or wandsman (British)) is a person, usually a layperson, who assists in the ordering of religious services, particularly in Anglican churches.

Etymology

The title of ''verger'' a ...

in the Duomo of Piacenza

Piacenza Cathedral ( it, Duomo di Piacenza), fully the Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta e Santa Giustina, is a Roman Catholic cathedral in Piacenza, Italy. The current structure was built between 1122 and 1233 and is one of the most valuable examp ...

; he was twenty-one when the judge Ignazio Gardini, of Ravenna

Ravenna ( , , also ; rgn, Ravèna) is the capital city of the Province of Ravenna, in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy. It was the capital city of the Western Roman Empire from 408 until its collapse in 476. It then served as the cap ...

, was banished, and he followed Gardini to Ravenna, where he met the vice-legate Giorgio Barni, who was made bishop of Piacenza

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of Episcopal polity, authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or offic ...

in 1688 and appointed Alberoni chamberlain of his household. Alberoni took priest's orders, and afterwards accompanied the son of his patron to Rome.

During the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

Alberoni laid the foundation of his political success by the services he rendered to Louis-Joseph, duc de Vendôme, commander of the French forces in Italy, to whom the duke of Parma

The Duke of Parma and Piacenza () was the ruler of the Duchy of Parma and Piacenza, a historical state of Northern Italy, which existed between 1545 and 1802, and again from 1814 to 1859.

The Duke of Parma was also Duke of Piacenza, except ...

had sent him. That a low-ranking priest was used as envoy was due to the duke's rude manners: the previous envoy, the bishop of Parma

The Italian Catholic Diocese of Parma ( la, Dioecesis Parmensis) has properly been called Diocese of Parma-Fontevivo since 1892.

, had quit because the duke had wiped his buttocks in front of him: Saint-Simon in his Mémoires relates that Alberoni gained Vendôme's favor when he was received in the same way, but reacted adroitly by kissing the duke's buttocks and crying "O culo di angelo!". The duke was amused, and this joke started Alberoni's brilliant career. When the French forces were recalled in 1706, he accompanied the duke to Paris, where he was favourably received by Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Vers ...

.

Middle years

Philip V Philip V may refer to:

* Philip V of Macedon (221–179 BC)

* Philip V of France (1293–1322)

* Philip II of Spain, also Philip V, Duke of Burgundy (1526–1598)

* Philip V of Spain

Philip V ( es, Felipe; 19 December 1683 – 9 July 1746) was ...

. Following Vendôme's death, in 1713 he was made a Count

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility. Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty''. New York: ...

and appointed Consular agent for Parma at Philip's court where he was a Royal favourite.

Under the terms of the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vacant throne o ...

, Philip became King of Spain but the Spanish Empire was effectively partitioned. The Southern Netherlands and their Italian possessions were ceded to the Austrian Habsburgs and Savoy

Savoy (; frp, Savouè ; french: Savoie ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps.

Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south.

Savo ...

, Menorca

Menorca or Minorca (from la, Insula Minor, , smaller island, later ''Minorica'') is one of the Balearic Islands located in the Mediterranean Sea belonging to Spain. Its name derives from its size, contrasting it with nearby Majorca. Its capi ...

and Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

went to Britain while British merchants gained trading rights in the previously closed market of the Spanish Americas.

At this time, the key powerbroker at the Spanish court was Marie-Anne de la Trémoille, princesse des Ursins who dominated Phillip and his wife Maria Luisa of Savoy

Maria Luisa Gabriella of Savoy (17 September 1688 – 14 February 1714), nicknamed ''La Savoyana'', was Queen of Spain by marriage to Philip V. She acted as regent during her husband's absence from 1702 until 1703 and had great influence as a ...

. Alberoni worked with her and when Maria Luisa died in 1714 they arranged for Philip to marry Elisabetta Farnese

Elisabeth Farnese (Italian: ''Elisabetta Farnese'', Spanish: ''Isabel Farnesio''; 25 October 169211 July 1766) was Queen of Spain by marriage to King Philip V. She exerted great influence over Spain's foreign policy and was the ''de facto'' rule ...

, daughter of the Duke of Parma.

Elisabetta was a strong personality herself and formed an alliance with Alberoni, their first action being to banish the Princesse des Ursins. By the end of 1715, Alberoni had been made a Duke and Grandee

Grandee (; es, Grande de España, ) is an official royal and noble ranks, aristocratic title conferred on some Spanish nobility. Holders of this dignity enjoyed similar privileges to those of the peerage of France during the , though in neith ...

of Spain, a member of the King's council, Bishop of Málaga

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

and Chief Minister of the Hispanic Monarchy. In July 1717, Pope Clement XI

Pope Clement XI ( la, Clemens XI; it, Clemente XI; 23 July 1649 – 19 March 1721), born Giovanni Francesco Albani, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 23 November 1700 to his death in March 1721.

Clement XI w ...

appointed him Cardinal, allegedly because of his assistance in resolving several ecclesiastical disputes between Rome and Madrid in favour of Rome.

One outcome of the war was to reduce the powers of Castile and Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to sou ...

and create a Spanish state similar to the centralised French system. This allowed Alberoni to copy the economic reforms of Colbert and he passed a series of decrees aimed at restoring the Spanish economy. These abolished internal custom-houses, promoted trade with the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America, North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World. ...

, instituted a regular mail service to the colonies and reorganised state finances along lines established by the French economist Jean Orry

Jean Orry (4 September 1652 – 29 September 1719) was a French economist.

Life Early career

Jean Orry was born in Paris on 4 September 1652 to Charles Orry, a merchant, and Madelaine le Cosquyno.

Orry studied law and entered Royal service ...

. Some attempts were made to satisfy Spanish conservatives e.g. a new School of Navigation was reserved for the sons of the nobility.

These reforms made Spain confident enough to attempt the recovery of territories in Italy ceded to Savoy

Savoy (; frp, Savouè ; french: Savoie ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps.

Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south.

Savo ...

and Charles VI of Austria

, house = Habsburg

, spouse =

, issue =

, issue-link = #Children

, issue-pipe =

, father = Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor

, mother = Eleonore Magdalene of Neuburg

, birth_date ...

. In 1717, a Spanish force occupied Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label=Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after ...

unopposed; neither Austria or Savoy had significant naval forces and Austria was engaged in the Austro-Turkish War of 1716–18. This assumed the British would not intervene but when 38,000 Spanish troops landed on Sicily in 1718, Britain declared it a violation of Utrecht. On 2 August 1718, Britain, France, the Netherlands and the Austrians formed the Quadruple Alliance Quadruple Alliance may refer to:

* The October 1673 alliance between the Dutch Republic, Emperor Leopold, Spain, and Charles IV, Duke of Lorraine, during the Franco-Dutch War.

* The 1718 alliance between Austria, France, the Netherlands, and Great ...

and on 11 August the Royal Navy destroyed a Spanish fleet off Sicily at the Battle of Cape Passaro

The Battle of Cape Passaro, also known as Battle of Avola or Battle of Syracuse, was a major naval battle fought on 11 August 1718 between a fleet of the British Royal Navy under Admiral Sir George Byng and a fleet of the Spanish Navy under R ...

.

Alberoni now attempted to offset British in the Mediterranean by sponsoring a Jacobite landing to divert their naval resources; he also sought to end the 1716 Anglo-French Alliance by using the Cellamare conspiracy to replace the current French Regent the Duke of Orleans with Phillip of Spain. However, he failed to appreciate that Britain was now powerful enough to maintain naval superiority in the Mediterranean and the Atlantic while France declared war on Spain in December 1718 on discovery of the Conspiracy.

France invaded eastern Spain and in October 1719 a British naval expedition captured the Spanish port of Vigo

Vigo ( , , , ) is a city and Municipalities in Spain, municipality in the province of Pontevedra, within the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Galicia (Spain), Galicia, Spain. Located in the northwest of the Iberian Penins ...

; they landed 6,000 troops, held Vigo for ten days, destroyed vast quantities of stores and equipment and then re-embarked unopposed. The nearby city of Santiago de Compostela

Santiago de Compostela is the capital of the autonomous community of Galicia, in northwestern Spain. The city has its origin in the shrine of Saint James the Great, now the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, as the destination of the Way of St ...

even paid £40,000 in return for being left alone. As intended, this was a crushing demonstration of British naval power and showed the Spanish Britain could land anywhere along their coastline and leave when they wanted to. The failure of his policy meant Alberoni was dismissed on 5 December 1719 and ordered to leave Spain, with the Treaty of The Hague in 1720 confirming the outcome of Utrecht.

Later years

He went to Italy, escaped from arrest at Genoa, and had to take refuge among the

He went to Italy, escaped from arrest at Genoa, and had to take refuge among the Apennines

The Apennines or Apennine Mountains (; grc-gre, links=no, Ἀπέννινα ὄρη or Ἀπέννινον ὄρος; la, Appenninus or – a singular with plural meaning;''Apenninus'' (Greek or ) has the form of an adjective, which wou ...

, Pope Clement XI

Pope Clement XI ( la, Clemens XI; it, Clemente XI; 23 July 1649 – 19 March 1721), born Giovanni Francesco Albani, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 23 November 1700 to his death in March 1721.

Clement XI w ...

, who was his bitter enemy, having given strict orders for his arrest. On the death of Clement in 1721, Alberoni boldly appeared at the conclave, and took part in the election of Innocent XIII

Pope Innocent XIII ( la, Innocentius XIII; it, Innocenzo XIII; 13 May 1655 – 7 March 1724), born as Michelangelo dei Conti, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 May 1721 to his death in March 1724. He is ...

, after which he was for a short time imprisoned by the new pontiff on the demand of Spain on charges including sodomy

Sodomy () or buggery (British English) is generally anal or oral sex between people, or sexual activity between a person and a non-human animal ( bestiality), but it may also mean any non- procreative sexual activity. Originally, the term ''sodo ...

( Elizabeth Charlotte of the Palatine noted in her diaries that he was a pederast

Pederasty or paederasty ( or ) is a sexual relationship between an adult man and a pubescent or adolescent boy. The term ''pederasty'' is primarily used to refer to historical practices of certain cultures, particularly ancient Greece and anc ...

). He was ultimately cleared by a commission of his fellow Cardinals. At the next election (1724) he was himself proposed for the papal chair, and secured ten votes at the conclave that elected Benedict XIII.

Benedict's successor, Clement XII

Pope Clement XII ( la, Clemens XII; it, Clemente XII; 7 April 16526 February 1740), born Lorenzo Corsini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 12 July 1730 to his death in February 1740.

Clement presided over the ...

(elected 1730), named him legate of Ravenna

Ravenna ( , , also ; rgn, Ravèna) is the capital city of the Province of Ravenna, in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy. It was the capital city of the Western Roman Empire from 408 until its collapse in 476. It then served as the cap ...

, where he erected the Porta Alberoni (1739), a magnificent gateway that formerly provided access to the city's dockyards, and has since been moved to the entrance of the Teatro Rasi. That same year, the strong and unwarrantable measures he adopted to subject the grand republic of San Marino

San Marino (, ), officially the Republic of San Marino ( it, Repubblica di San Marino; ), also known as the Most Serene Republic of San Marino ( it, Serenissima Repubblica di San Marino, links=no), is the fifth-smallest country in the world an ...

to the papal states incurred the pope's displeasure, and left a historical scar in that place's memory. He was soon replaced by another legate in 1740, and he retired to Piacenza

Piacenza (; egl, label= Piacentino, Piaṡëinsa ; ) is a city and in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy, and the capital of the eponymous province. As of 2022, Piacenza is the ninth largest city in the region by population, with over ...

, where in 1730 Clement XII appointed him administrator of the hospital of San Lazzaro, a medieval foundation for the benefit of lepers

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease (HD), is a long-term infection by the bacteria ''Mycobacterium leprae'' or ''Mycobacterium lepromatosis''. Infection can lead to damage of the nerves, respiratory tract, skin, and eyes. This nerve damag ...

. Since leprosy had nearly disappeared in Italy, Alberoni obtained the consent of the pope to suppress the hospital, which had fallen into great disorder, and replaced it with a seminary for the priestly education of seventy poor boys, under the name of the Collegio Alberoni, which it still bears. The Cardinal's collections of art gathered in Rome and Piacenza, housed in his richly appointed private apartments, have been augmented by the Collegio. There are remarkable suites of Flemish tapestries, and paintings, among which the most famous is the ''Ecce Homo'' by Antonello da Messina

Antonello da Messina, properly Antonello di Giovanni di Antonio, but also called Antonello degli Antoni and Anglicized as Anthony of Messina ( 1430February 1479), was an Italian painter from Messina, active during the Early Italian Renaissance. ...

(1473), but which also include panels by Jan Provoost

Jan Provoost, or Jean Provost, or Jan Provost (1462/65 – January 1529) was a Belgian painter born in Mons.

Provost was a prolific master who left his early workshop in Valenciennes to run two workshops, one in Bruges, where he was made a burgh ...

and other Flemish artists, oil paintings by Domenico Maria Viani and Francesco Solimena

Francesco Solimena (4 October 1657 – 3 April 1747) was a prolific Italian painter of the Baroque era, one of an established family of painters and draughtsmen.

Biography

Francesco Solimena was born in Canale di Serino in the province of ...

.

Alberoni was a gourmand

A gourmand is a person who takes great pleasure and interest in consuming good food and drink. ''Gourmand'' originally referred to a person who was "a glutton for food and drink", a person who eats and drinks excessively; this usage is now rare. ...

. Interspersed in his official correspondence with Parma are requests for local delicacies ''triffole'' (truffles

A truffle is the fruiting body of a subterranean ascomycete fungus, predominantly one of the many species of the genus ''Tuber''. In addition to ''Tuber'', many other genera of fungi are classified as truffles including ''Geopora'', ''Peziza ...

), salame

Salami ( ) is a cured sausage consisting of fermented and air-dried meat, typically pork. Historically, salami was popular among Southern, Eastern, and Central European peasants because it can be stored at room temperature for up to 45 days ...

, robiola cheeses, and ''agnolini

Agnolini are a type of stuffed egg pasta originating from the province of Mantua (in the Mantuan dialect they are commonly called "agnulìn" or "agnulì") and are oftentimes eaten in soup

or broth.

The recipe for Agnolotti was first publis ...

'' (kind of pasta). The pork dish ''" Coppa del Cardinale"'', a specialty of Piacenza, is named for him. A ''"timballo

Timballo is an Italian baked dish consisting of pasta, rice, or potatoes, with one or more other ingredients (cheese, meat, fish, vegetables, or fruit) included. Variations include the mushroom and shrimp sauce ''Timballo Alberoni'', named after ...

Alberoni"'' combines maccaroni, shrimp sauce, mushrooms, butter and cheese.

Death and legacy

He died leaving a sum of 600,000ducat

The ducat () coin was used as a trade coin in Europe from the later Middle Ages from the 13th to 19th centuries. Its most familiar version, the gold ducat or sequin containing around of 98.6% fine gold, originated in Venice in 1284 and gained wi ...

s to endow

A financial endowment is a legal structure for managing, and in many cases indefinitely perpetuating, a pool of financial, real estate, or other investments for a specific purpose according to the will of its founders and donors. Endowments are of ...

the seminary

A seminary, school of theology, theological seminary, or divinity school is an educational institution for educating students (sometimes called ''seminarians'') in scripture, theology, generally to prepare them for ordination to serve as clergy, ...

he had founded. He left the rest of the immense wealth he had acquired in Spain to his nephew. Alberoni produced many manuscript

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand – or, once practical typewriters became available, typewritten – as opposed to mechanically printing, printed or repr ...

s. The genuineness of the Political Testament, published in his name at Lausanne

, neighboring_municipalities= Bottens, Bretigny-sur-Morrens, Chavannes-près-Renens, Cheseaux-sur-Lausanne, Crissier, Cugy, Écublens, Épalinges, Évian-les-Bains (FR-74), Froideville, Jouxtens-Mézery, Le Mont-sur-Lausanne, Lugrin (FR-74), ...

in 1753, has been questioned.

References and sources

;References ;Sources * * Kuethe, Allan J. "Cardinal Alberoni and Reform in the American Empire." in Francisco A. Eissa-Barroso y Ainara Vázquez Varela, eds. ''Early Bourbon Spanish America. Politics and Society in a forgotten Era (1700–1759)'' (Brill, 2013): 23–38.''Catholic Encyclopedia'':

Giulio Alberoni

Giulio Cardinal Alberoni

Conclave of 31 March – 8 May 1724

Collegio Alberoni, Piacenza

{{DEFAULTSORT:Alberoni, Giulio 1664 births 1752 deaths People from Fiorenzuola d'Arda 18th-century Italian cardinals Grandees of Spain